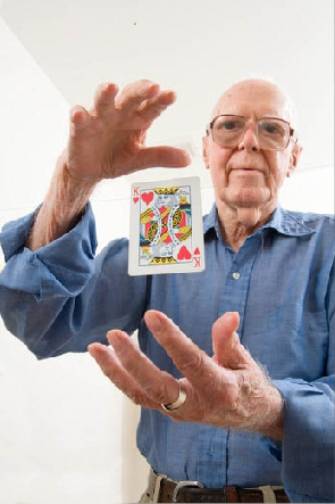

Conversations with Martin Gardner, May 2007.

Donald E. Simanek.

Martin Gardnerís name is well known to mathematicians and scientists, as well as laymen who enjoy puzzles and games. From 1956 to 1981 he authored the ďMathematical GamesĒ column in Scientific American. These columns were collected in 15 books. He has written over 70 books including short stories, novels, critiques of pseudoscience, and books explaining esoteric science for the layman. His books The Ambidextrous Universe, The Annotated Alice, and Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science have become classics. His is a mind that knows few boundaries. At the time of this interview, having just passed his 92nd birthday, Martin was still busy writing. He died May 22, 2010.

WRITING

DES You have had a long career in writing, and have won much acclaim for your work. How did you get started in writing?

MG My first job was as a reporter for the Tulsa Tribune. That was shortly after I got out of college. That was good training because you had to meet deadlines. I had the great title of "assistant oil editor" of the Tulsa Tribune. I was there for a year or so, then I went back to the University of Chicago and eventually got a job in the press relations office. My job was to write science releases, which were sent out to local newspapers.

The first time I got any money for writing was after I got mustered out of the Navy and I went back to the University of Chicago. I could have gotten my old job back in the press relations office, but I sold a short story to Esquire magazine. Much to my delight I got actually paid for it. It was a humorous story titled "The Horse on the Escalator." It was the story about a man who collected jokes about horses. He thought they were hilarious but his wife didn't think any of them were funny. But she pretended she thought they were funny and laughed every time he told a horse joke. That was the basis for my story. The title came from a joke that was going around at the time about a man who entered the Marshall Fields department store with a horse. At that time elevators all had elevator operators. The operator said "You can't take the horse on the elevator." The man replied, "But lady, he gets sick on the escalator." It is in a collection of my short stories, most of which are from Esquire, called "The No-Sided Professor." The title story was one of the earliest science fiction stories based on topology. I was paid a little better for that. Then for about a year I lived on sales of fiction to Esquire magazineĖabout 12 stories. Then Esquire got a new editor and moved from Chicago to New York city, and I lost my market. The new editor didn't think my stories were funny.

DES Most writers are avid readers. I know you are. What authors do you most enjoy and respect?

†

MG One of my favorite authors is Lord Dunsany (1878-1957). He was an Irish Lord and a famous writer of fantasy. Sometimes when I have written a fantasy story I've tried unsuccessfully to imitate his style. I have a collection of every Book Dunsany wrote.

I was in love with fantasy when I was a very young boy. My favorite reading was L. Frank Baum. I read all 14 Oz books, and about the same number of non-Oz fantasies that Baum wrote.

DES Did you read Alice in Wonderland when you were a child?

MG I read Alice in Wonderland when I was very young, and I didn't like it. I found it a little bit frightening, and I didn't appreciate the Alice books until I was a young man.

DES Some say the book isn't for children, certainly not for today's children.

MG I can't imagine a young child, say under 17, getting much of anything out of the two Alice books.

DES Do you suppose children in Lewis Carroll's day did?

MG Apparently they did. The books were a big hit with children.

DES Your book The Annotated Alice is probably the best-selling book you have written. Whatever motivated you to take on such a large project?

MG I was very much interested in Lewis Carroll and the two Alice books. It occurred to me that they were so filled with jokes and allusions that a child in England would have understood in the Victorian age, but no modern American child, or even an adult, would. I suggested to a couple of publishers that they write to Bertrand Russell and ask him to annotate the two books. I knew he was a big fan of Lewis Carroll. One publisher actually did write to Russell, and he said "No." He was too busy with other things. I mentioned it one day to Clarkson Potter who was a young editor who had just started working for Crown. He said to me "Why don't you do it." I thought about it for a while and said "Well, I'll give it a try."

DES It must have required a tremendous amount of research.

MG That's right. I went to the library and read everything I could about Lewis Carroll, and I reported to Potter that I would make an effort to do it. That's how the first book came about. By the time I had agreed to do it Potter had moved from Crown and started his own company called Clarkson Potter Inc., and that was one of his very first books.

SCIENCE

DES Were you interested in science at an early age?

MG Yes. Partly because my father was a professional geologist, with a Ph.D. in geology, who wrote many technical papers, mostly about limestone caverns. From my father I got a big dose of geology. He was also interested in astronomy. I learned from him the order of the planets from the sun. When I was in grade school I even constructed a model of the solar system, with pictures of the planets pasted on a cardboard, with a crude drawing of their orbits. I think that may still be in storage somewhere. So, my first interest in science was mainly through my dad's influence.

DES Magazines such as Science and Invention were popular in the 1920s. Were you a fan of these?

MG I was a big fan. Science and Invention was the delight of my youth. Partly because of the type of articles they ran and partly because they had a science-fiction story in every issue. They had a series called "Dr. Hackensaw's Secrets". Each one was a science fiction story, and there were 40 of them that Gernsback published. When he started Amazing Stories magazine, it was advertised in Science and Invention, and I was a charter subscriber. I've often regretted that I didn't save the first 12 issues. I gave them all to my high school physics teacher. He was interested in reading them, and also made them available to his class. I had been in his physics class and he had a big influence on me. I made very poor high school grades in history and English Lit., but I got good grades in physics and math. I got A's in geometry and algebra. My father bought me a copy of Sam Loyd's Cyclopedia of 5000 Puzzles, Tricks, and Conundrums, and I was hooked on recreational math.

DES Did you read Scientific American back then?

MG No, I didn't.

DES You wrote the "Mathematical Games" column in Scientific American for 25 years, and that material found its way into 15 books. How did that job come about? Did you realize what you were getting into?

MG No, I had no idea. I was living in New York at the time. After Esquire moved to New York I realized that New York was the place for a free-lance writer, so I pulled up stakes and moved to New York. I had great difficulty earning a living. Then Humpty Dumpty magazine came along. A fellow named Harold Schwartz was in charge of their children's books. He happened to be a personal friend, and he hired me to do activity features for Humpty Dumpty, which was just getting started. For eight years I was a contributing editor. In every issue I did a short story about Humpty Dumpty giving moral advice to Humpty Dumpty Junior. They were eggs of course. The magazine came out ten times a year. So I did 80 stories, which never found a book publisher.

I also did the activity features, where you do something that damages the page. You cut it, you tear it out, you fold it, you hold it up to the light. You make a slot and slide a strip up and down through it. These were unsigned. That was great fun. I stopped doing Humpty Dumpty only when I started the Scientific American column.

FUTURE SCIENCE

DES Those 1920s science and invention magazines often speculated on the future of science and technology. Very often they got it wrong, failing to anticipate important innovations. You are now 92 years of age, and have seen a lot of new things emerge from science. What scientific breakthroughs were most unexpected to you?

MG Television was certainly one of them. I remember as a boy when the first television began to be available I was really awed by it. When it started out the pictures were rather crude, but they got better and better. And of course, the computer revolution was another.

DES Do you care to speculate about the next big breakthroughs in science?

MG I suppose the biggest breakthrough in computer science would be quantum computers. They'd be so much faster they would open up all kinds of possibilities.

DES Will artificial intelligence ever duplicate or surpass the human mind?

MG I'm convinced it will not. I belong to a school of thought called the Mysterians. It's a name applied to about a half dozen philosophers. We are convinced that the human mind, consciousness and free will, are so profound and difficult to explain that no one has the slightest idea how the brain does it.

DES I think it was Von Neumann who said that if we ever make computers that can think, with the power of the human brain or better, we won't know how they do it either.

MG Well, that's true. It may be possible that computers will imitate human intelligence in some far distant future. I don't think those computers will be made of wires and switches.

DES What if we allow them to learn by themselves and make mistakes? Don't humans learn by making mistakes?

MG We do. But some kind of threshold is crossed when a computer becomes aware of its own existence. The name "consciousness" applies to that. That is a major threshold that I don't think any computer that we know how to build will cross. I can imagine in a far future if a computer were made of organic material it might be able to imitate a human brain, but as long as its made of electrical currents and switches I don't think it will cross the threshold. I've written a number of articles about that.

MATHEMATICS

DES You have been called a "mathemagician" for your many articles on mathematics and magic. I understand that if someone names just about any number you can find interesting things about that number.

MG Maybe.

DES Your fictional Dr. Matrix had that ability. Is there any number that is devoid of anything interesting? If so, that fact alone would make it interesting, wouldn't it?

MG That's right. That's a famous paradox.

DES Your Dr. Matrix stories created quite a stir when you wrote about his research facility for the study and application of psi-org energy near Pyramid Lake, Nevada.

MG I hadnít realized that a lot of people would take it seriously. I got a complaint from some Nevada authorities because people were trying to find the spot where Dr. Matrix was working. To get there they had to travel along a narrow and dangerous road.

DES Were you aware of the remoteness of the place before you wrote the piece?

MG No, I didnít know that. The state was complaining that my column caused people to drive on roads they shouldnít have been on. A lot of readers took Dr. Matrix to be a real person. I used to get letters addressed to him.

DES Your fictional Dr. Matrix was supposedly an expert on numerology and other esoteric magical arts. Have you discovered any new numerological mysteries recently?

MG I recently ran across a strange number coincidence that I hadnít known before.† If you take the digits 0 through 9 and arrange them in alphabetical order, which is a completely artificial order, you get eight, five, four, nine, one, seven, six, three, two, zero, or 8549176320. Divide it by five and you get 1709835264, a ten-digit number in which all ten digits appear. Someone posted this on the Internet as a totally useless fact. It doesnít lead to any significant mathematics.

DES Does Dr. Matrixís name have any significance, beyond the obvious reference to mathematical matrices?

MG The name Irving Joshua Matrix was chosen because each of the three names spell with 6 letters, so you get 666, the famous ďnumber of the beast.Ē I have big files on the number 666.

DES Dr. Matrix had a beautiful Eurasian assistant, Iva Toshiyori.

MG† I needed an oriental sounding last name. I looked at a map of Tokyo and saw a street named Toshiyori that sounded like a great name for Iva. I got called on that by a reader from Japan, who inquired whether Dr. Matrix and Iva were real people. He said that Toshiyori was a very peculiar surname, for it means ďthe street of the old manĒ.

DES In 1998 you revised and modernized that classic and somewhat subversive book Calculus Made Easy by Silvanus P. Thompson. There's much hand wringing amongst mathematics teachers about whether and how to reform the teaching of calculus, since many students take the course but don't really learn it well enough to use it effectively. Can you give them any advice on this matter?

MG My only advice is to read Silvanus Thompson. I still think that's the best book to give a high school student to introduce him to calculus. It's written with a good deal of humor, and approaches the subject in a very simplified way. I think a student can learn calculus better that way than from a big, huge textbook.

LOGIC

DES Many people place unwarranted faith in logic, and think logic can generate truths.

MG I donít think formal logic gives you much information about the external world. But it teaches you how to make statements that arenít inconsistent. If you understand formal logic it makes it easier for you to eliminate inconsistencies in what you say.

DES Itís the cement with which we hold arguments together.

MG Thatís true.

DES Mathematics is just a branch of logic.

MG Thatís true. Or you can say logic is a branch of mathematics.

MAGIC

DES You have written a huge book, The Encyclopedia of Close-Up Magic, and also articles for magician's magazines. When did you first become interested in magic?

MG Again I have to go back to my father. He was not a magician at all, but he taught me a few magic tricks when I was very young, that he did very skillfully. One involved a table knife on which he put little bits of paper on the two sides. One at a time you pretend to remove the bits of paper until the knife is empty on both sides, then you wave it and the bits of paper come back again. It uses what magicians call the "paddle move". It was the first magic trick I ever learned. There was a trick where you put a match on a handkerchief, break the match, then open the handkerchief and the match is unbroken. That fooled me completely when he did it. There was another match hidden in the hem of the handkerchief. That's the one you really broke.

DES Were you ever a performing magician?

MG No. The only time I was a performer was when I was in college. I worked Christmas seasons at Marshall Field, in the toy department, demonstrating Mysto Magic sets. They had a series of sets with different degrees of complexity, and there was one in particular that had very nice equipment in it. I worked out a routine and did magic behind the counter until a crowd collected. I went through a series of tricks using equipment in the magic set. I did that for about three Christmas seasons working from Thanksgiving day through Christmas eve. That's the only time I ever got paid for doing magic.

DES During your time in Chicago, did you know any of the legendary Chicago magicians?

MG Oh, I did. Magic was my principal hobby and I used to spend a lot of time socializing with the magic crowd. In the evenings they gathered at a Chinese restaurant called the Nankin. There were 6 to 12 people. I used to take the elevated into town and join the crowd at the Nankin restaurant, or another restaurant where they met on Saturdays. So I got acquainted with all the Chicago magicians. Also a number of magicians who were playing a Chicago date would appear at the restaurant as guests. So I got to meet a lot of out of town magicians also. Most of the magicians worked in nightclubs.

DES In your columns and books you revealed several magician's tricks that are based on mathematics. The Gilbreath principle was one. What's the simplest trick you could recommend to our readers that uses this principle?

MG The simplest trick is to pre-arrange the deck so the card colors alternate red black red black. If you are skilled at false shuffles you can pretend to shuffle the deck. There are various ways to appear to shuffle the deck without disturbing the order. You can do an overhand shuffle and take the cards one at a time, which leaves the red-black sequence intact. Then you hand the deck to someone, instructing them to cut the deck and give it just one good riffle shuffle. Let them fan the cards and look at them, to ensure that they are well mixed. Instruct the person to cut the cards between two cards of the same color and complete the cut. Take the deck under the table, out of sight. Propose that your sensitive fingers can tell red from black, and you will select pairs, one of each color. Bring out the top two cards from the deck and it's a red-black pair. Keep doing this repeatedly. The point is that one riffle shuffle doesn't destroy all order in the deck. In this trick it leaves the cards in red-black pairs. At least 8 riffle shuffles are necessary and sufficient to destroy all order in a deck. That was first proved by a good friend of mine, Percy Diaconis, now a prominent statistician.

DES You once showed me a trick with four cards securely bolted together, yet the order of the cards changes when you manipulate them. I have since extended that idea to use more cards in order to confound physics students. What was the original context of this as a magic trick, and do you know who invented it?

MG I don't know who invented it. It just suddenly appeared on the magic market, sold in magic stores. The point was that you spread the bolted cards, showing that they are alternating in color. Then you rotate the fan and the two black cards are together and the two red cards are together.

[Weíll reveal the secret of this neat deception in a separate article in this issue.]

OTHER INTERESTS

DES You have diverse interests, mathematics, magic, visual illusions, science, pseudoscience, logic, philosophy, and religion. Is there any theme hereĖanything that connects them all?

MG I don't know.

DES It seems to me that they all have the element of paradox, the conflict between perception and reality. Logical paradoxes, visual illusions, and magician's tricks all present something that appears to defy what is possible in the real world. And many forms of pseudoscience assume things that can't possibly happen in the real world.

MG I think you've hit on it. That's probably the common denominator.

DES I read somewhere that among your many talents, you are a performer on the musical saw. Can that really be true?

MG Thatís true. Thatís one of my hobbies. I play it almost every few days. I take it off the hook and tap out some simple tunes.

DES Do the neighbors complain?

MG So far they havenít. The walls are pretty thick here.

DES Have you ever been asked to play publicly?

MG No, gosh no. I refuse to play for guests because Iím so poor at it, but I get a little better, and it amuses me.

DES Thereís some interesting physics in that instrument.

MG I havenít advanced to the point where I bow it. I hit it with a little mallet that has a felt tip on the end. Itís smoother if you bow it, but you need a cello bow. They are very expensive and you have to keep putting rosin on the saw. So I donít bother with bowing it, but you can get a pretty good sound by tapping it. You have to bend it into an S shape. You wiggle one leg up and down to give it vibrato.

PHILOSOPHY

DES You were a philosophy major at the University of Chicago. The job market for philosophers wasn't good even then. Did you have a career goal in mind?

MG No, I didn't. I was interested in philosophy mainly to find out what my own beliefs were. On the first day of the first class I took, the professor asked everybody why they were taking that course. I was the only one who said I took it to find out what I believed. The rest of the class laughed. I never intended to be a teacher. If you were majoring in philosophy, that gave you an excuse to dabble in any other subject if you want. The University of Chicago was at that time under what they called the "new plan" and you could audit any course, not for credit, but you could sit in on the class. I took full advantage of that. I think I audited more courses than I was taking for credit.

DES You left graduate school early, without seeking an advanced degree. Can you tell us the reason?

MG I took just one year of graduate school.

DES Had you found out what you believed by then?

MG I was beginning to find out what I believed. The most important course I ever took was after the end of the war, under the GI bill, which paid my tuition. I took one course, from Rudolf Carnap, the famous Viennese philosopher, a member of what they called the "Vienna circle". That really hooked me on the philosophy of science. It was the most important course I ever took. Several years later Carnap had moved from the University of Chicago to the University of California. I wrote him and asked if it was possible to have his course tape-recorded, and would he allow me to edit it into a book that we would collaborate on. I sent him a copy of my short story, "The No Sided Professor", so he saw that I could write. He agreed. His wife sat in class and tape-recorded the lectures, then sent me the tapes. I edited them into the book Philosophical Foundations of Physics, later changed to Introduction to the Philosophy of Science. This is a book I took great pleasure in writingĖas much as anything I have ever written. The ideas were Carnap's, but the actual writing was mine.

DES How much did his course influence your own philosophy?

MG It influenced me enormously. It convinced me that most metaphysical statements were meaningless.

DES One website refers to you as a "hard-core Platonist". What's your philosophical position on the question of "reality"?

MG Well, in the first place I'm a realist. I believe the external world exists independent of the human mind. I also believe that about mathematics. I think that mathematics exists independent of human intelligence. That's what makes me a Platonist. Actually I prefer the term "mathematical realist". Also, and this may surprise you, I'm a philosophical theist. I depart completely from Carnap in that respect. Carnap was an atheist.

DES For those of our readers who havenít read your 1983 book The Whys of a Philosophical Scrivener, can you explain how your belief in an external world of physics and mathematics, as well as your belief in God, can be compatible with your view that most metaphysical questions are meaningless?

MG I think metaphysical questions are meaningless in that you canít have any actual knowledge about their truth. There are certain things that are emotionally of value. I think you can justify a belief in God on the basis that it gives you a great deal of† emotional satisfaction. This is called the emotive theory of truth. Either a person has an emotional basis for wanting to believe in God or they have no such basis. You canít argue between the two. For example, I say I believe in God but I donít know that God exists. I have absolutely no knowledge that God exists; I have no proof that He exists, or any evidence that God exists. But you are faced with the choice of thinking that the entire universe has absolutely no meaning whatever, itís just an accident that happens from time to time. Thereís this big bang in which nothing explodes into a universe. That has absolutely no meaning whatsoever. That leaves you with a rather bleak view of life. If that doesnít satisfy you emotionally, you can make a leap of faith and posit the existence of a deity. Only you have no cognitive knowledge of the existence of God.

I believe making a leap of faith has a genetic basis. Itís now a very popular point of view even amongst biologists who are atheists. Religious faith is endemic to almost every culture. Thereís no culture known that doesnít have some type of religious view. You have to explain how it is that this is such a universal phenomenon. Thereís speculation now that it has a small amount of survival value. If a person makes a leap of faith it provides them some kind of consolation and hope for another life. That might make them a little happier and better adjusted and give them some survival value. Thatís of course purely speculative.

DES That would infuriate creationistsĖto think that belief and religion might have an evolutionary basis.

DES Doesnít a lot hinge on your definition of ďbeliefĒ? When I say, ďI believe it will rain todayĒ Iím not talking about the same thing as saying ďI believe in God.Ē

MG Your belief that itís going to rain today can be backed

up by empirical evidence. Thereís absolutely no evidence that God exists.

Atheists, I think, have all the better arguments. In fact thereís a good deal

of evidence that God doesnít exist. If there is a God, presumably heís

benevolent, and yet thereís this massive irrational evil in the world. An

earthquake can kill 10,000 people. Thatís a very strong argument against the existence of God. If you make a leap of

faith, itís really against the evidence.

DES I imagine your

belief doesnít have much in common with the organized religions.

MG Absolutely not.

DES Most of them

demand something like an ďindustrial strengthĒ belief, a belief that admits no

possibility of being wrong.

MG Thereís a statement I like to quote from Gilbert Chesterton. ďTo an atheist, the universe is the most exquisite masterpiece ever constructed by nobody.Ē The leading American exponent of the emotive theory was William James. He wrote a famous essay called ďThe Will to BelieveĒ.

PSEUDOSCIENCE

DES Probably your second most acclaimed book is Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science, which has been in print ever since 1952. It has earned you the title of "debunker" of pseudoscience. One of your books even has "debunking" in its title. Some people don't like that term. They think it denotes a biased attitude and a mind that is not sufficiently open. Are you comfortable with it?

MG Yes, I don't mind the term. I not only think it's a good term to use, but I think all professional scientists should do a certain amount of debunking in their field. A lot of them are so busy that they don't want to bother. One of the few exceptions was Carl Sagan, who wrote a couple of books you can call debunking books.

DES You are associated with groups that have "skeptic" in their name. Can you clarify what "skeptic" means to you, and what you would define as "healthy skepticism"?

MG As far as scientific matters are concerned, the main reason for being a skeptic is that you should not believe anything unless there's sufficient evidence.

DES Richard Feynman said that scientific method consists of procedures we have learned to help us avoid drawing wrong conclusions.

MG That's a good definition.

DES Your book had a chapter on the flat earth theory.

MG I once heard Wilbur Glenn Voliva lecture in a local church in Chicago, arguing for the flat earth. Literature was being given out by some of his assistants. I marveled at the fact that they were very young and beautiful young ladies. It was hard for me to imagine that they would be members of such a crazy church.

DES What was his appeal?

MG I donít know. He struck me as a perfect example of a crazy crank. He gave a serious lecture citing all sorts of evidence that the earth was flat.

DES Your book also had a chapter on perpetual motion. The idea of making a machine that puts out more energy than it takes in has been persistent since the 11th century, and shows no sign of abating. Today some folks are pinning their hopes on tapping the "zero point energy" and "dark energy" that speculative theoretical physics are talking about. They say that the laws of physics, particularly the laws of thermodynamics, stifle creativity, and delay the time when we will produce unlimited energy for next to nothing. How would you respond to them?

MG Well the question of whether you can tap zero point energy is a very technical question in quantum mechanics. I'm not enough of an expert to know exactly the reasons for not believing it. So I have to base my opinion on that of the experts. Most experts in quantum mechanics believe that it's impossible to get any usable energy that way. Besides, the amount of energy is very small. I respect their opinions. The leading exponent of zero point energy is Harold Puthoff, who is one of the two scientists who verified the psychic powers of Uri Geller. I have little respect for Puthoff. He's comparable to a person searching for a perpetual motion machine made of whirling wheels.

DES Did you get a lot of correspondence from the targets of your book?

MG I got quite a bit of correspondence.

DES You once told me of a clever strategy you used with two folks who asked you for your opinion on their perpetual motion machine ideas.

MG I mainly used that on angle trisectors. If I got a letter from an angle trisector I would reply "I'm not competent to judge your construction, but you should write to so-and-so, he's an expert on it." I'd give him the name and address of another angle trisector.

DES I'll bet you never heard from either of them again.

MG That's true.

DES Back in the 18th century such people were called "paradoxers".

MG The mathematician Augustus de Morgan (1806Ė1871) wrote a large book titled Budget of Paradoxes about circle-squarers and others of that sort.

DES You have also been critical about some mainstream science, such as string theory. How does a non-scientist make judgments when reading about such things? How can one draw the line between science and pseudoscience? Are there any useful clues or characteristics that one can identify?

MG It's technically called the "demarcation problem"--the problem of distinguishing good science from bad science. There obviously isn't any sharp line. It's very difficult to decide sometimes whether a scientist is just a maverick scientist who may hit on something new or whether he's a crank. String theory is a case in point. I really have no business criticizing string theory because I don't understand it too well.

DES Our mutual friend, Bob Schadewald, said that pseudosciences were entertaining, and mostly harmless, except for one. The one he thought "dangerous" was creationism. Are any others dangerous?

MG Another area of pseudoscience that's really harmful is pesudo medical science. A person can get hooked on something like, say, homeopathy. Clearly there's absolutely no scientific basis for a homeopathic drug being of any value at all because it's diluted to the point where there isn't any of the drug left. A basic dictum of homeopathy is that the more dilute the drug, the more potent it is. They dilute the drug until there are only a few molecules of it left, or not even that. A homeopathic drug has absolutely no therapeutic effect, but if a person believes the drug is effective it can have a strong psychological effect. A person who is hooked on homeopathy can start relying on the drugs and not go to a reputable doctor, when he might have a serious illness. People could die.

DES A while back Jacques Benveniste (1935-2004) rationalized homeopathy by claiming that water had a memory of anything that was once dissolved in it.

MG My friend James Randi was involved in debunking him.

DES If that were true, then any tap water we drink would have memory of everything that was ever in it, poisons, medicines and everything else not taken out at the treatment plant. A glass of tap water would be as beneficial as a homeopathic medicine.

MG When Randi gives a lecture, he produces a bottle of a homeopathic remedy made from a chemical which, when taken in quantity, is poisonous. He drinks the entire bottle in front of the audience.

DES Philosophial "why" questions have great appeal, and generate many best-selling books. All such questions force us to speculate beyond the bounds of the observable universe. Is such effort important, or is it futile?

MG There are certain philosophical "why" questions that are obviously impossible to answer. "Why is there something rather than nothing?" Or, as Hawking put it, "Why does the universe bother to exist?" "Why is the universe the way it is and not some other way?" There's no way to answer such questions, but they can have profound emotional effect. If you think about them too long you can go mad.

DES What do you think of the various forms of the antrophic principles? Wasn't it you who coined the term C.R.A.P., the "Completely Ridiculous Anthropic Principle"?

MG I don't think much of the anthropic principle. But some of the string theorists are taking it very seriously now. One of the strongest arguments against evolution is the argument from design. In its modern form, the argument says that some 20 physical constants have to be so fine-tuned that if they had other values you couldn't have a universe, you couldn't have galaxies, and you couldn't have planets. A number of string theorists postulate an infinite number of universes, each with a different set of physical constants, as a way of getting around the fine-tuning argument.

DES Is this physics, or is it philosophy?

MG I think it is philosophy.

DES You introduced John Horton Conway's "game of life" to the world in your Scientific American column. This was a computer simulation game that showed the consequences of very simple rules governing the behavior of counters on a very large or even infinite grid.

MG That was one of my most successful columns.

DES That computer simulation shows that from just a few simple rules, complex, persistent structures with lawful and orderly behavior can and often do arise. It demonstrates that order and lawfulness can arise without purposeful design.

MG That's one of the great lessons you get from the game of life.

DES This goes a long way toward demolishing a cherished belief amongst creationists that lawfulness and order equal design and design requires a designer. Is that a fair assessment?

MG Absolutely.

DES We recently learned that a number of those seeking to be President of the USA have said they donít believe in evolution. Creationist movements, were once primarily a USA phenomenon, but are now arising in other parts of the world. I know you have written on this, and many books on both sides of the issue appear every year. What do you suggest as the appropriate way for scientists to deal with this issue? Many scientists used to ignore it.

MG A good many scientists are not willing to testify in states that are trying to pass laws demanding that creationism be taught in the public schools. Fortunately some are willing to get involved.

DES Thatís the legal issue. But do scientists have any responsibility to better educate the general public?

MG Absolutely. You have to start in the lower grades in high school. Evolution should be taught in every high school biology class.

DES But then thereís the way itís taught. So much of education is criticized for emphasizing learning of facts and slogans without understanding. Some say it is indoctrination. How do we counter that? When evolution is taught in the schools it is often badly taught.

MG Itís very hard to get good science teachers. The pay is very low. Some science classes are taught by teachers who have no background or training in science. Theyíve gone to teachersí college and majored in history. Somebody says ďWe need somebody to teach science 101 and youíre it.Ē They try to keep a week ahead by reading a textbook. But they have no understanding or enthusiasm for science. The students are bored by a teacher who really doesnít understand what sheís teaching.

DES What is your take on the newly spawned offspring of creationism: "Intelligent Design"? Some say that even though ID is clearly not science, it is at least an interesting philosophical idea. Do you agree?

MG It is a legitimate theory, itís just that there isnít any evidence that God is tinkering with the evolutionary process and thereís no need for Him to do so. I like to point out that thereís no need for God to tinker with the solar system to keep the planets on track. Why should it be necessary for God to tinker with evolution when random mutations combined with survival of the fittest will do the trick? There just isnít any need for a God hypothesis to explain how evolution works.

DES Could there possibly be any evidence that would come from experiment that would indicate that a supernatural intervention had occurred at some point in evolution?

MG Itís hard for me to imagine how that could happen.

DES If there were such an event, and a gap that could not be explained by natural processes, what would that tell us? Nothing.

MG Thatís right. The intelligent design people like to point out that even on the lowest levels of life, the complexity is irreducible. Thatís Michael Beheís idea. In a lot of cases biologists and geologists donít presently know what the intermediate steps are. But the point is the steps could be there, and we should work to find out what they are.

DES Many times in the history of science we didnít know details that we discovered later.

MG Thatís the way science works. Creationists donít understand that.

DES What advice can you give to aspiring writers? You once quoted Bertrand Russell's advice.

MG He said that whenever he thinks of a simpler word that can be substituted for a complicated word, he always adopts the simpler word. I try to follow that advice.

[end]

The photo is © by Adam Fish.