Proofs of Unknowables. The Proof is Pudding.

|

THE PARADOX OF LIFE Philosophical grook.

A bit beyond perception's reach

|

|

Proofs for a creator.

Some ten or more standard arguments are typically bought forth by defenders of religion—arguments cast in the form of logical "proofs" of the necessity of a god, or the existence of a god. Though it seems a waste of space to print them here, I shall anyway, because the only place one can find them on the www is at religious sites. [Some sites expand the list to "100 proofs", but close examination shows tremendous duplication padded out by many that are trivial by any standard.] So it's instructive to see them all in one place exposed in all their naked silliness.

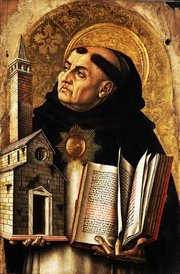

- Prime Mover argument. [St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica]. Motion requires a mover. Any mover must also require a mover. This sequence would extend through an infinite number of movers (infinite regression), and therefore is absurd. So therefore there must be a "first mover, moved by no other", that is, a god.

- First Cause Argument. [Thomas Aquinas] All effects in the universe have causes. The universe itself must have had a cause. But this again is an infinite regression to infinity, which is absurd. Therefore one must assume a "first cause", that is, a god.

- Possibility and Necessity Argument. [Thomas Aquinas] In nature things exist or do not exist. But in the realm of the possible, anything could exist. But not everything can be in the realm of the impossible, for then there would be nothing. If at one time there were nothing, then the universe could not have come into existence. So we must assume the existence of at least one being that exists by its own necessity, not receiving necessity from any other, but causing in others their necessity. This is a god.

- The Perfection/Ontological Argument. [Thomas Aquinas, first presented by St. Anselm] There are gradations from lesser to greater good, truth and nobility. Therefore there must be something with a maximum of these qualities. This must be the cause of their being, goodness and perfection. This is a god. [Anselem defined a god as "something then which nothing greater can be conceived." Anselem then clobbered the unbeliever as a "fool", citing Psalm 14:1, "The fool hath said in his heart, there is no god").]

- The Design/Teleological Argument. [Thomas Aquinas] Since bodies in nature act toward some outcome or "end", even though they lack knowledge, then some intelligent being must have provided them with "orders" for action. "Therefore some intelligent being exists by whom all natural things are ordered to their end, and this being we call God." [This is obviously the earlier form of the present-day "Argument from Design.]

- The Miracles Argument. The miracles of the Bible are suspensions or violations of natural law, therefore they must have been caused by a supernatural power. That power is God.

- Pascal's Wager Argument. Blaise Pascal had a "mystical experience" at age 30 that began his serious preoccupation with religion. He was not satisfied with the usual arguments for a god, and he saw that those arguments had absolutely no effect on skeptics; therefore he wanted a "convincer" argument to bring people to God. The result is an argument known as "Pascal's Wager". Pascal was very much interested in the mathematics of gambling, and wrote on the subject. His argument goes like this. If we wager that God does not exist and he does, then we have everything to lose and nothing to gain. If we wager that God does exist and he does, then we have everything to gain and nothing to lose. That's it. Rather a disappointment of an argument, isn't it? Well, Pascal did make some important contributions to mathematics, even if this contribution to theology was a bust. This is the "Even if it might not be true, play it safe and believe in it" argument.

- The Mystical Experience Argument. Essentially, "I know God exists because I had a mystical experience (or conversion, or vision, etc.)." [This is the "my hallucinations must be truth" argument also used by persons who claim to be Jesus Christ, Napoleon, or George Washington. Nowadays such persons are generally institutionalized, but sometimes they found institutions, like religions.]

- Fideism, or the Credo Quia Consolans argument. Essentially, "I believe because it feels right, makes me feel good, or consoles me." [This is the "feel-good" argument.]

- The Moral Argument. Human beings are capable of moral judgments, animals are not. This "moral sense" must have come from a supernatural being. That is God. This argument has a twin. "Without God there would be no morality and people would do whatever they want, and would do evil, for there would be no reason to be otherwise." [In short, "It's good to believe in an invented fantasy, if it makes you a better person."]

|

All of these have unsupported premises, undefined or poorly defined concepts and even logical gaps. Not one carries the slightest weight. Therefore they are easily shown to be invalid, and refutations of them are found in many books. Yet the defenders of religion still use them to clobber nonbelievers, apparently unaware that they are using blunt and broken weapons. How anyone can with a straight face present these as valid arguments is beyond me.

Notice the frequent use of the word "therefore" in these proofs, standing between two things that are in fact not logically dependent. This is the "does not follow" fallacy.

All of these arguments for a god have common faults, and once that fact is exposed, any further examination of the arguments is unnecessary, pointless, and a waste of time.

|

- The arguments assume that logic can tell us about an entity that may not be limited by logic.

- The arguments assume that laws and principles we know to operate "within" the universe also apply broadly even "outside" of the universe (whatever that might mean), to entities imagined to exist independently from the universe.

- The arguments assume that we can deduce something about an entity postulated to be greater than the universe and greater than any human being, using the limited resources of our imperfect and finite minds and our limited experiences.

- All of the arguments claim to establish the existence of a supernatural being or entity, then equate it to the traditional "god" entity, without independently defining that entity or proving it to be the same thing as "god".

Actually the first three of these are, as we would say in science, "unwarranted extrapolation" from limited data, into a domain about which we know nothing.

The bottom line: The proofs of the existence of a god are pathetic attempts to justify an emotional commitment to a fantasy that is logically and scientifically impossible to prove. Once this fact is appreciated, all of these proofs of a god are seen to be totally empty of content.

|

This has been known since St. Thomas Aquinas formulated some of these arguments and others promptly refuted them, conclusively. Some people, however, never seem to learn. We now see these same arguments resurrected with "intelligent designer" substituted for "God". That makes no difference at all. The arguments are still specious.

Arguments of this sort do not convince people to accept the notion of a god. They are not the reasons that people believe. These arguments are only used by folks who already believe in god, in hopes of convincing others to believe. They were invented as an atempt to rationalize an already-existing irrational belief. For one who has no pre-existing belief, these arguments carry no persuasive power.

Exercise for the reader. Using our four "faults of reasoning", demolish each of the ten "proofs for a deity". Easy, isn't it?

Are these arguments worth the trouble of refuting?

The detailed individual refutations of "proofs" of a god are, perhaps, yielding too much to theists, for the refutations are often cast using the same logic as the "proofs" themselves, and sometimes even implicitly accept the questionable premises that the religious apologists use. Some say we should rather criticize the very process of attempting to use pure logic to attempt to prove anything about the universe. Certainly we scientists know that is futile and unacceptable. But the critics of theism are not debating with scientists. To use a person's own methods of argument to refute his argument is a worthwhile thing to do. It ought to shift the argument to other grounds if both parties are thinking rationally.

Also, I would quibble that the word "proof" is entirely inappropriate here. Proof is something you do in pure logic and pure mathematics, which are symbolic systems that by themselves tell us nothing about the so-called "real world" of experience, and certainly nothing about the supernatural. Mathematics can serve as a descriptive modeling tool in science, and a very powerful one. But the laws and theories of science are limited by the always not-quite-perfect data. When scientists are careful with their language, they never claim to "prove" anything in science and never claim "absolute truths" of any kind. This is a point many non-scientists do not appreciate.

|

Theists aren't always careful with the their use of the concepts of "truth" and "proof". But if they are going to claim to make any argument from scientific premises, they had better play the science game correctly. For the same reason that science cannot claim proofs and truths, so theists cannot use science to claim proofs and truths.

So let's leave proof and truth out of the discussion and simply ask, "Are any of these arguments for a god or intelligent design even suggestive or plausible or at all persuasive of the possibility of a god?" Not at all. Of course, one could argue that "anything is possible" so long as you don't have to supply credible evidence for it. That's what fairy tales and science fiction do.

Nor do the theists have any cause to shift the argument to the skeptics and demand "Prove that a god can't exist." Sorry, no one can do that any more than anyone can prove that a god could exist.

|

Since there's no evidence nor reason to even suppose that there's a god or intelligent designer, and no way to establish that there isn't, what should one believe? Well, why should anyone believe anything about that question? If there's no way to do something, then it's foolish to try to do it. If there's no way to answer some questions, then why invent answers and engage in futile efforts to justify those answers? While one could imagine a god, or many gods, or many other fantastic illusions, why should one do so? And, why should one (as some do) carry it one step further and "believe" in such an imagined entity? I mean the "industrial strength belief" of religions, the belief that will not even entertain the possibility that the belief could be wrong.

|

So am I saying one isn't justified in believing anything? That's exactly what I'm saying; though remember that I'm talking about "absolute belief", or theistic belief. Of course I believe the sun will (probably) rise tomorrow, and I believe that if you were to jump naked from a very tall skyscraper you have scant chance of surviving. But these are weaker beliefs, the kind of provisional belief we have in certain well-established scientific principles and observations, justified because we have good evidence that nature's behavior is lawful and reliable. We can have very strong confidence in certain regularities of behavior of things we observe. Here we are dealing with things in the universe apprehensible to our senses. But when we talk about things not accessible to our senses nor to any method of experimental observation, we are totally unjustified in holding absolute beliefs of any kind about them.

|

Scientists are not about to found a religion based on their "belief" in the law of gravitation. Science can get along quite well without ever using the words "belief" and "truth". Religious beliefs have no use in science, and science tells us nothing about the beliefs of religions.

Am I saying the universe has no purposeful designer and no purpose? No one can say one way or the other. But all the evidence of our experience indicates that the universe operates quite well without purpose. There is no evidence of any "driving purpose" in nature. Does this mean that our lives are without meaning? That, is, I think, a meaningless question, upon which far too much ink has been wasted.

|

We ought to accept and try to understand the universe that we can observe, and can discover some useful things about. The universe is all we know or can know, all else is unverifiable fantasy. We ought to be content to live with that fact and make the best of it.

To sum up, religions are emotionally appealing invented fantasies. Their claims can't be proven or disproven, nor is there any evidence that is even suggestively supportive of their claims. Religions would be relatively harmless if only people didn't believe in them.

- —Donald E. Simanek, Feb 3, 2006.

Intelligent Design Creationsm: Fraudulent Science.

The Evolution Deniers.

Intelligent Design: The Glass is Empty.

Order from Disorder. Creation in Everyday Life.

Random Thoughts on Randomness.

Is The Real World Really Real?

Uses and Misuses of Logic.

The Scientific Method.

Theory or Process?

Is Intelligent Design an Interesting Philosophical Idea?

Why not Angels?

What's bugging the creationists?

Summary and Conclusions.

Return to Abuses of science.

Return to Donald Simanek's home page.