![[Graphic: Inkwell

labeled VITRIOL © John Holden]](vitriol.gif)

Uncle Don's Notebook16 July 2002Each of us needs a notebook in which to jot down those flashes of insight, one-liners, bad jokes, Nobel-prize-worthy ideas, and provocative tidbits and scraps read or heard. This is mine.This document is the natural successor to my regular column Scraps From The Editor's Wastebasket in The Vector, published from 1976 to 1991.

Signs of Boredom [Aug 2002]

We got suckered by reviewers into seeing the movie Signs. That

Newsweek cover story on director Shyamalan may have had some

influence, too. Now I've seen some bad movies in the past. Nashville,

Magnolia, The Mask and Welcome to the Dollhouse sit

at the bottom of the barrel of movies I should have walked out on. This

new stinker isn't that bad, but it leaves a bad taste just the same.

Signs is a shameful exploitation picture, mining cliches from many

movies of the

past. Close Encounters of the Third Kind (also a dissappointment) comes

to mind. The movie's several explicit references to War of the Worlds

just remind us that that was a better story (though not a great movie).

Here we have the theme of the kid with asthma, which is surely a set up for

something later in the picture, and also

the other kid with the water purity phobia. The ex-minister who has lost his

faith is another cliche, but when he regains it, it's totally unclear what

in this story motivated that.

Then there's things which just don't add up.

We have an alien trapped in a kitchen storage

closet, inexplicably lighted well enough so that the closet's

contents and the alien are

visible in the reflection of a kitchen knife. Water is poisonous to the

aliens, so why do they come so far across space to a planet which has so

much of this poison? And how did they survive for several days without

clothing or protective suits? Were they having a drought all over the world,

so they never got caught in the rain? And for all the business about

crop circle designs all around the world, we never got a believable explanation

of why the aliens should do that. I could go on, but why dignify this

proliferation of cliches by discussion?

This movie is an insult to the intelligence of moviegoers. The director/writer

has slickly thrown together elements from other (and better) movies, tried

to give them some "logical" connections, but not out of any conviction or

passion for the story.

They are used only to manipulate the popcorn munchers in the audience.

This is a cold exercise by a director who would like to be a Spielberg or

Hitchcock, but hasn't the intelligence to do it.

Perpetuum Mobile [Aug 2002]

Since I created web pages called

The Museum of Unworkable Devices

I've gotten a surprising amount of email from people who submit their

pet perpetual motion machines for analysis. Apparently many people

tinker with this in their spare time. These are not con-artists like

Dennis Lee, but simply folks who like to construct machines for their

own amuseuemt. Everyone needs a hobby, they say.

My pages are somewhat different from most other books and web pages

about perpetual motion. I treat each case as a puzzle, the object being

to find the flaw in physics or reasoning which prevents the device from

working as the inventor intended. It's always a simple misapplication of

elementary physics. So these puzzles are useful ways to test and

strengthen one's ability to apply physics principles.

But even when I do this, some inventors still have faith that their idea

can be made to work by some modification or other. It's a triumph of

blind faith and hope over reason and experiment.

I find it noteworthy that most of these proposals come to me with no

calculations, equations or experimental measurements to support the claims.

Many are no more than pencil-and-paper

exercises, totally unsupported by any laboratory experimentation. One person

did offer to send me a set of blueprints! I told him a simple sketch

and description would be quite enough.

One person hinted that my pages do a disservice, for by showing all those

examples of machines that don't work I am discouraging inventors and

stifling their faith and optimism as they try to devise perpetual motion

machines that do work. Well, repeated failure does that, too.

Every perpetual motion machine inventor I've encountered

is also religious. This isn't surprising. The religious mindset, especially

that of the Christian Fundamentalist, doesn't really trust science, and

firmly believes that "With God, all things are possible." The scientist

has learned better, that nature does some things with relentless regularity,

but refuses to do certain other things. Science is the process of determining

what nature does, and how it does it, and what things nature does not do.

Nature is under no obligation to behave as we'd like it to. No amount of

faith, hope or perseverance can alter the fundamental laws of nature.

Our time is better spent trying to find out exactly how nature does

work, then exploit that understanding to accomplish new and useful things within

those limitations.

The folks who hope to make machines with unlimited energy output bristle at

the laws of thermodynamics, which are usually stated in a manner which tells

us what isn't possible in nature. They don't like "negative" statements of laws.

But every law of physics does that. A law which specifically tells

us precisely what will happen in certain circumstances is also telling us

what will not happen.

What's new? [Aug 2002]

Again, my lame excuse for neglecting these Notebook entries is that

I've been making additions to my other web pages. For example:

When I was a teenager I

experimented with the family box Brownie camera, and later with

my first $15 folding camera which took 120 film. I shot close-ups,

stereos (by moving the camera horizontally)

and panoramics (by taking overlapping

pictures, then carefully cutting and dry-mounting the prints into a

picture four feet long).

All that has changed now that photography has gone digital. Digital

pictures taken in an overlapping sequence can be stitched together

with software. I've just discovered some remarkable software to do that:

PanaVue.

It can alter the perspective of the pictures cylindrical

or spherical (your choice), stitch the pictures together, blend the stitch

area and do color correction.

It can usually do all this automatically. But you can

do it manually if necessary. The results? Well, here's one:

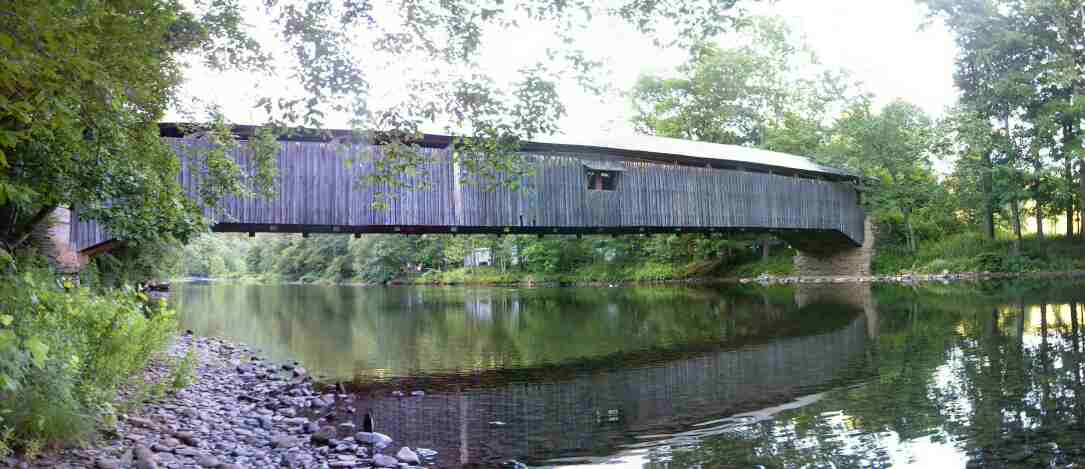

I photographed this Pennsylvania covered bridge with an inexpensive digital

camera in very low lighting conditions. The only good vantage

point was too near the bridge for an ordinary camera lens to see more than

about 1/5 of the span of the bridge. So I shot seven pictures, overlapping.

This picture covers only a modest visual angle, but

the PanaVue system can assemble much larger panoramics,

even up to 360°, horizontal, vertical, or any other way, and even

stitch photos in a matrix (useful for aerial photos). I give this

software four stars.

The Fundamentalist Mindset [July 2002]

The tragic events of last November ought to stimulate a sober re-examination of

the perversion of religion by fundamentalists of all stripes and the dangers

of religious fanaticism and religious dogmatism. But instead it

has fueled the flames of religious conservatism in our own country.

It has encouraged

zealots who wish to impose prayers and their own brand of religious instruction

into our public schools,

and who seek to reaffirm the religious symbolism which has already

corrupted our government and political life, such as the "under God" addition

to the "Pledge of Allegiance".

As an outsider to religion, these trends are alarming to me.

Fundamentalist religion of any variety has one central characteristic.

The fundamentalist is passionately convinced of the "rightness" of his

or her beliefs.

The fundamentalist is right, and everyone else is wrong.

This isn't a matter of opinion or reason

for the fundamentalist, but is a matter of divine inspiration.

Once one has that conviction, most any actions against nonbelievers can

be justified, for unbelievers are by definition, wrong.

While such religious fundamentalists

may live relatively peacefully with neighbors of other religious views in

secular countries which respect diversity, they look for any opportunity

to seize control of the social or government structure

and bend it to their own beliefs.

And when they are in a position of power, any respect for other views

vanishes.

It's easy enough to say that the fundamentalist fanatics who engage in terrorism

have "perverted" their religion, and easy for us to

dismiss their actions as aberrations.

But what spawned their particular religious views?

Every fundamentalist religion

is an offshoot of a "mainstream" religion, and every "perverted" belief of

a fundamentalist has its roots in elements of mainstream religious thought.

Have not these mainstream religious had their own sordid history of

violence, injustice, inhumanity and intolerance?

Have we forgotten the crusades, the

inquisition, and even the Jim Jones and Heaven's Gate tragedies of recent past?

What religion today can claim an unblemished record?

The root problem is belief itself—the

kind of belief which admits no possibility of being wrong.

This is industrial-strength religious belief. Most religions

encourage unquestioning belief, considering such belief to be a necessary,

noble and desirable thing. I consider it to be

the root cause of many of the evils which mankind has inflicted upon itself.

"Belief" is a word with many shades of meaning. We say "I believe

it's going to rain today."

That indicates no more than a probability of something

happening. The scientist, in casual conversation, may say "I believe in the

laws of mechanics." This represents a "provisional" or tentative belief,

saying that so far as any experiment has shown,

these laws seem to work, and they have theoretical

underpinnings in other laws which are well tested and also seem to work.

The scientist

admits that future scientific developments may cause us to modify these laws

to accommodate new discoveries, so his "belief" in the laws isn't absolute.

But the belief of the religious person, particularly the fundamentalist, is fundamentally

different. For fundamentalists, religious belief is considered

absolute, and religious

"truths" are not subject to test or verification—they can never

be refuted by any experiment, event, or argument. The "true believer"

knows they are right because they feel right. It's an

emotional, not a rational commitment, though many believers are quite adept

at concocting rational-sounding arguments (rationalizations) to support their

convictions

in arguments with non-believers. Theology is the "academic" manifestation

of this empty exercise in apologetics.

In my view, such absolute beliefs are not only dangerous, but

they are totally unwarranted. We simply have no way to discover or test

absolute truths. We can only invent them, then believe them, then impose

those beliefs on others. The ancient Greeks spoke often of the

impossibility of finding absolute truths:

But as for certain truth, no man has known it,

Though some of this country's founding fathers were of religious inclination

(many of these were Deists),

they knew very well the "tyranny of religion" as practiced in Europe.

They sought to

invent a government immune from the abuses which religion, allied with

government, can inflict upon those who think differently. Their motives

were sound, and we benefit from their efforts. But they probably did not

imagine how their work would be eroded and compromised by the

religious fervor of later centuries.

Religious symbolism and slogans were added to our coinage,

to our oath of allegiance, prayers are said at government functions,

many seek to inject religion into education, and

politicians of all parties pander to religious voters. It is a shameful

exercise of the religious majority's oppression and suppression

of minority views,

so shameful that even sober and responsible religious leaders have spoken

against it. But they are in the minority, especially in these times of

patriotic excess.

Amidst the furor of press coverage of the "under God" phrase in the

pledge of allegiance, one voice

of reason stood out. Anna Quindlen (whose commentary is usually insightful)

wrote in Newsweek (July 15, 2002, p. 64) reminding Americans

that the pledge arose late in our history, in 1892, and the words

"under God" only added by act of Congress in 1954 during the excesses and

fervor of the "Red scare". She was one of

the few journalists brave enough to point out the obvious:

The news is filled with corporate accounting scandals, corporate bankruptcies,

and continually declining stock market performance. Discouraging, yes, but surprising?

It shouldn't be. For quite a few decades the conventional 'wisdom' was a vision

seen through rose-colored glasses of a booming economy, continued growth and general

good times ahead. People forget that such things are cyclic, if history is any

indicator. Yes, history does repeat itself, but usually when you least

expect it.

Of course we blame this whole mess on greedy CEOs, insider information sharing,

and a lack of ethics at the higher levels of corporate management. It's not

that simple. Corporate greed is nothing new in our history; look at the

machinations of the 19th century robber barons.

Overlooked is something I see as a central issue in all of this. The stock

market has always been a gambling game, and those who think they have magical

"systems" for beating it are deluding themselves. Any system works when things

are booming, if you have enough cash for a stake in the game. The trick is

to keep things booming. Since those who run this gambling establishment also have

a stake in it, it's to their advantage to make things look as if they are booming

even if they aren't. So clever accounting is used across the board to make

everyone think that all is well, all is rosy, even when it's actually stagnating,

or even if it's on the way down the tubes. It's an elaborate game of self-deception

which pays off for those heavily invested in it, if they are privy to knowledge that

the average dupe investor can't obtain.

The bottom line is that this economic boom of the last few decades was largely

a paper fraud. Everyone involved, from the corporations to the government had

an interest in perpetrating the illusion, and no incentive to blow the whistle.

At the same time many new investors entered the market (buoyed by hopes of

fantastic returns), some of them invested through mutual

funds and their pension plans, totally innocent of the real state of affairs.

But it didn't take a crystal ball to see signs that the economy was not as

healthy as it was pictured. Many saw, and said, that a downturn or worse

was to be expected, but no one could pinpoint precisely when.

In the meantime, let's invest and get rich.

All of the classic con-games take advantage of human greed.

But of course, this illusion produced real financial gains—for a while.

Most scams and con-games do.

Good returns spur one to invest more and more, and suck in other investors,

which all fuels even better returns, until it all falls flat. We've seen this

in the past, with the notorious economic "bubbles" of the 18th centuries which

almost brought down some European governments. We would do well to read

Charles Mackay's classic 1841

"Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds." The latest

reprint edition I've seen (Bonanza Books) has a new foreword by Andrew Tobias.

How appropriate.

Even now some optimistic "experts" predict a recovery. If there is a recovery,

it will be a slow one and may be short-lived, for the economic fraud of recent

decades managed to hide very

entrenched weaknesses in our economy (and the "global economy")

which won't be quickly fixed by new regulations

on accounting, and won't respond to mere hype and hope.

Return to Uncle Don's Notebook Archives

|

Entries are stacked in reverse order, with the most

recent ones first, so readers won't have to wade through old

ones to get to the new ones. Occasionally they will be

collected and archived.

Entries are stacked in reverse order, with the most

recent ones first, so readers won't have to wade through old

ones to get to the new ones. Occasionally they will be

collected and archived.