|

Putting a spin on a puzzle. |

|---|

The title of this department defines its content. But sometimes it's not easy to decide which toys, tricks or puzzles to include. Of course, any that are new to me seem appropriate, but a little research may reveal that they are not as novel as I thought. A puzzle that I've never seen may be dismissed as "old hat" by puzzle collectors, who may tell me "Any serious collector will know that one." I may even discover that it was commercially marketed in various forms. A physics demonstration may cause a physics teacher to comment, "That one was discussed in one of the physics journals, oh, maybe 15 years ago," with an implication that "Every physics teacher knows it, so it's not worth discussion." Magic tricks are often marketed, but seldom patented. Anyone who is a bit curious can find out the secrets of both small tricks and large stage illusions with a trip to the library. When you start digging you discover that very few of these things are new, and many have precedents going quite far back in history. So I am resisting dismissive reactions from insiders. What's common knowledge among experts is not necessarily known to the general public, and just might be of interest to quite a few MAKE readers. Some may be inspired to make the devices I discuss here, or something like them, perhaps improving the idea in the process. The rest can skip this and move on to all the other good stuff in this magazine.

Many puzzles are based only on geometry or topology. A few require a principle of physics for their solution, and these have a special appeal for me. I especially like puzzles that have everything out in the open and there are no hidden mechanisms. Naturally I like puzzles that people have constructed with their own hands.

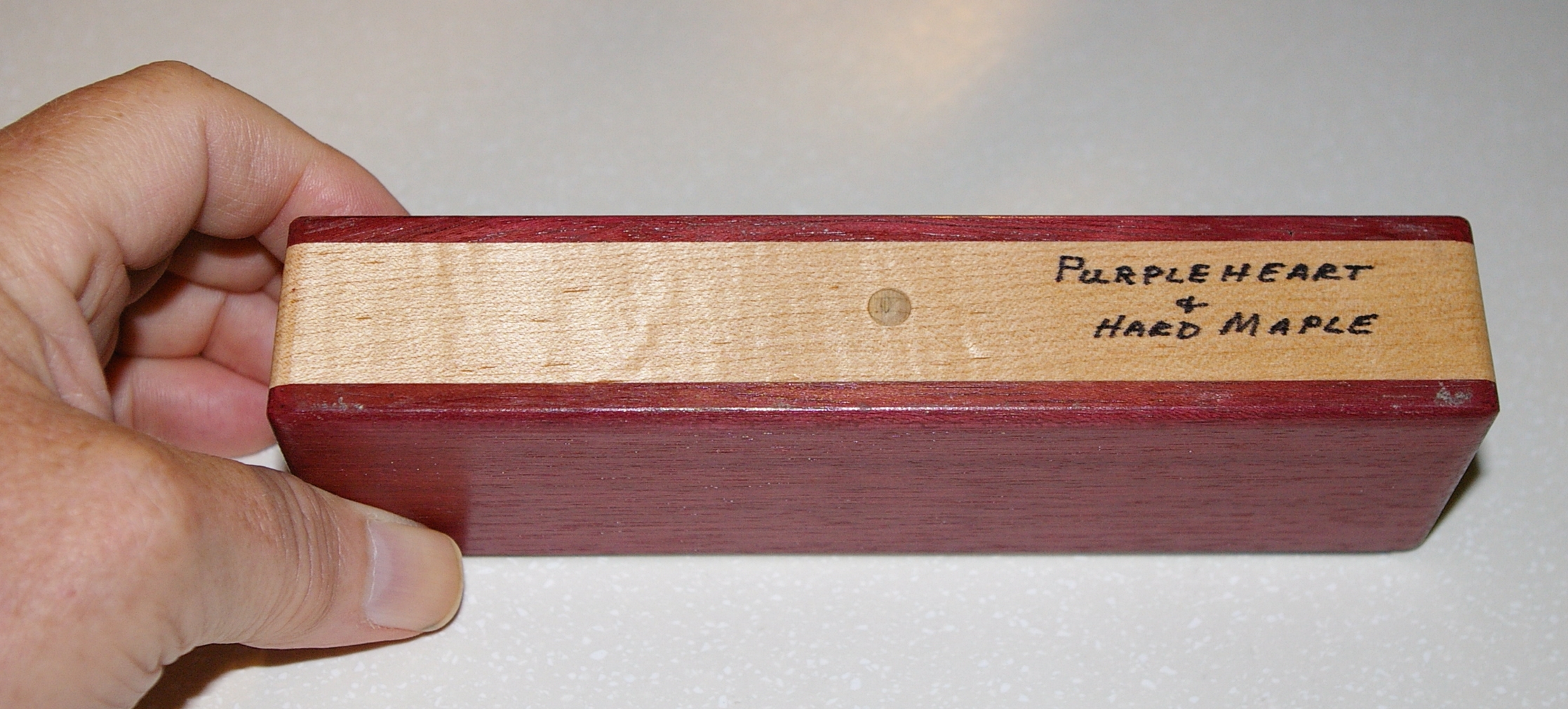

Here's a puzzle shown to me by Mary Nienhuis, a retired high school mathematics teacher. It was made some years ago by Paul Hooker, an industrial arts instructor at West Ottawa High school in Michigan.

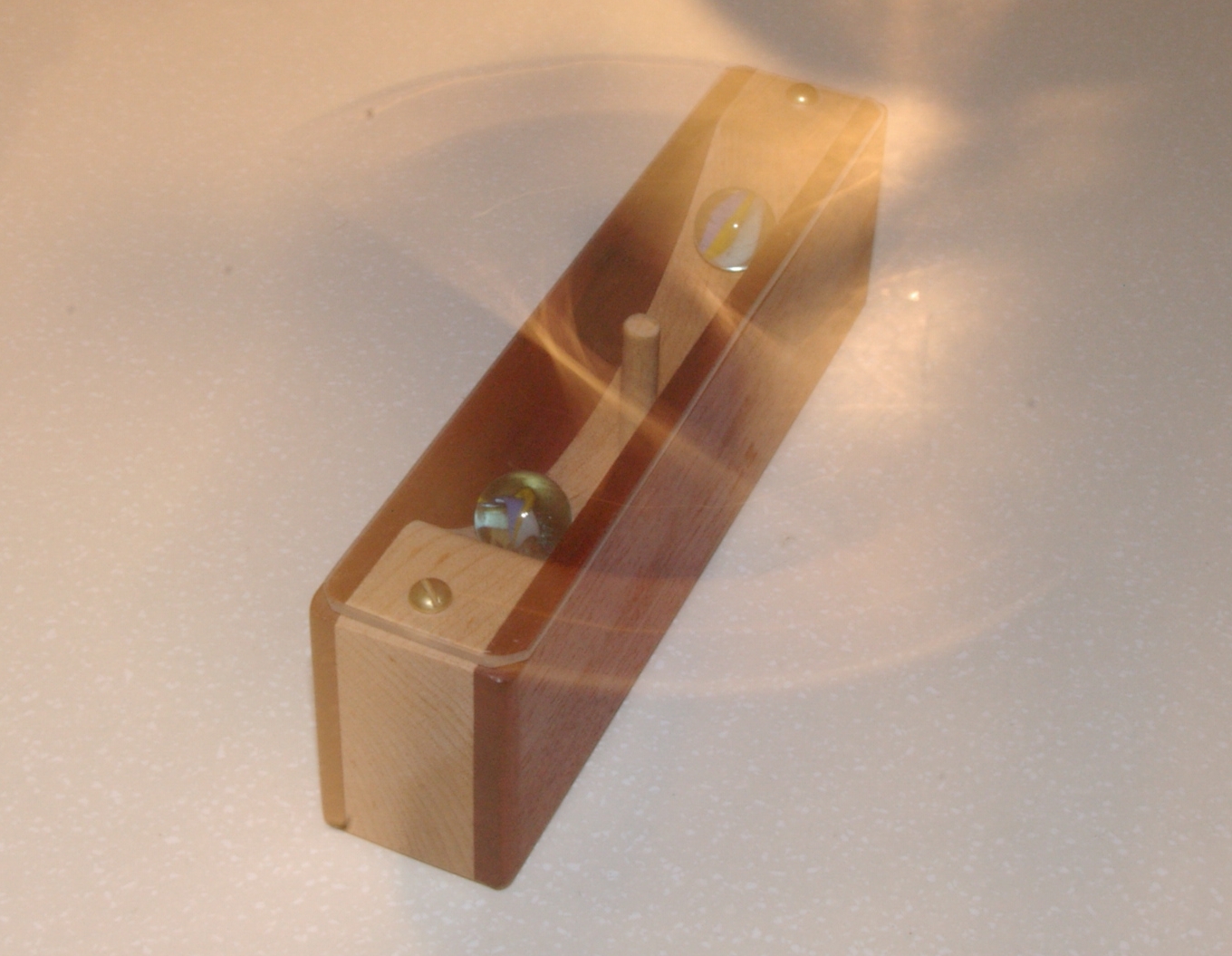

The construction is of red heart and hard maple (it says so on the bottom), with a transparent lucite cover that allows you to see two marbles inside, separated by a wooden dowel. The marbles can move on curved ramps that have a depression partway up each slope. The object is to get both marbles to rest in those two depressions—simultaneously. Tilting or shaking the puzzle does no good. You can easily get one marble into its hole, but any attempt to get the other one in just dislodges the first one.

Solution

Close examination reveals that the dowel in the center goes all the way through the maple piece and protrudes just a bit from the bottom. There it is rounded just a bit. This provides a pivot so that the entire puzzle can be spun, like a top, on a smooth surface, causing the marbles to rise up the ramp and settle into their respective depressions. The puzzle must be constructed so that it is very well balanced about that pivot point.

|

| The protruding dowel. |

|---|

|

| Spinning for a solution. |

|---|

This homemade puzzle is the cleanest and most elegant application of this principle that I've seen. So far as I know, this particular design has not been marketed. Anyone who enjoys woodworking can easily make one, or use the idea in other designs.

|

| All Uphill puzzle by Thinkfun. |

|---|

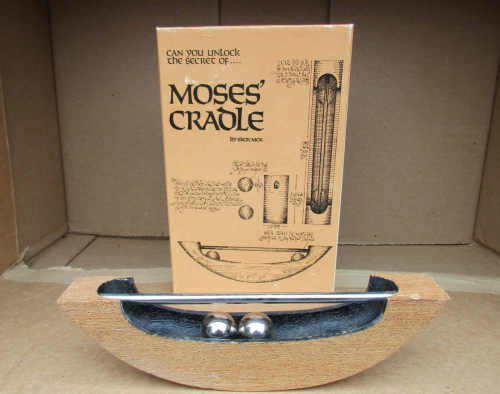

Quite a few classic puzzles employ spinning as part of their solution. Marketed puzzles of this sort include Skor Mor's "Moses' Cradle", Journet's "Spoophem", and the Adams "Dipsy Ball". Thinkfun's "All Uphill" is still available in a low cost (just a few dollars) plastic version.

|

| Moses' Cradle by Skor-Mor. Photo by Kennedy How |

|---|