2D to 3D Conversions.

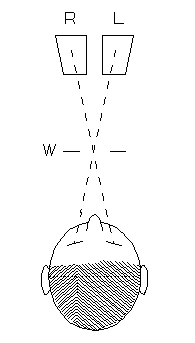

This page requires a monitor width of at least 1000 pixels in order to see both images for cross-eyed stereo viewing. Since the photos also have large vertical dimension, it helps to toggle the "full screen" view (F11 in Windows). However, if you haven't mastered that viewing method, these pictures may also be appreciated as 2D flat photos. All are © 2008 by Donald Simanek.For instructions on free-viewing 3d by the cross eyed method, see the How to View 3D page.

Fake Stereo.

The current proliferation of 3D movies has stimulated significant improvements in computer software to facilitate conversion of 2D source material to 3D. It is now less expensive to convert a 2D movie to 3D than to make it properly, from scratch, in true stereo 3D. Anyone can now buy such software (and some is free). Most such tools have a steep learning curve. Several commercial services can do the job for you, for a price.

Fireworks.

One of the challenges of still photography, especially stereo photography, is fireworks displays. Consider:

- You never know what the fireworks look like till it is too late to take the picture.

- You cannot anticipate exactly where the bursts will be.

- The bursts are usually quite far away, and may require a telephoto lens.

- As the display progresses, the sky gets clouded with smoke.

- The best firework photos include several bursts in one shot.

In 3D you have the problem of stereo baseline. Since the fireworks are so far away, the usual 2.5 inch stereo baseline is nowhere near large enough. So you will need to use two cameras separated farther apart, always aimed at the same place in the sky. If the fireworks are one mile away, you'd need a baseline of 176 feet to satisfy the 1/30 rule. And don't forget, these cameras must have synchronized shutters.

Many years ago I experimented with this method, using two identical Kodak Pony film cameras on either end of a 10 foot alumimum bar. The fireworks were on the other side of the river, about a mile away. It was a windy evening, and the cameras were somewhat shaky, even though on tripods. This is clear in the way the bursts' streamers are deflected by the wind, the streamers being "wiggly". I considered the experiment a failure, and did not return to it.

| Photo by Donald Simanek. |

Mounting and aligning the film chips was a real pain. The picture above was digitally copied from the original mounted stereo slide, then realigned with StereoPhotoMaker. The stereo baseline is much too small, so the stereo relief is weak.

So what can be done if you want better 3d results such as this?

| Photo by Donald Simanek. |

This picture was taken from a distance of about three miles, from our back porch, looking across town and across the Susquehanna river. Obviously it was a time exposure, including three firework bursts. A Pentax digital SLR was used with a 300 mm telephoto lens and a cable release to prevent vibrations. It was in fact a 2D shot converted later to 3D. Sorry to disappoint you.

I took advantage of an offer of three free 2D to 3D conversions that came to me by email. I submitted this picture as a challenge, fully expecting that the conversion would be a dismal failure, or that they would take one look at it and give up. The complicated intermixing of three colored bursts, and the nice white spots that give a sparkly effect ought to confuse the heck out of automatic 3D conversion software, or so I thought. But when I got the results back a few days later, I was amazed.

I've long been lukewarm to 3D conversions, whether they are movies or still photos. But there are situations where they may be the best solution to an otherwise difficult 3D scene, or when you have only a 2D photo of a scene you can't reshoot.

The other pictures I submitted for conversion included a portrait (very good results) and a visual illusion (failed miserably). I don't hesitate to recommend that you take advantage of their trial offer of three free picture conversions. I can't guarantee how long that offer will last.

For information, see William3d.

The bottom line for successful fireworks stereos is—fake it.

Other conversion examples.

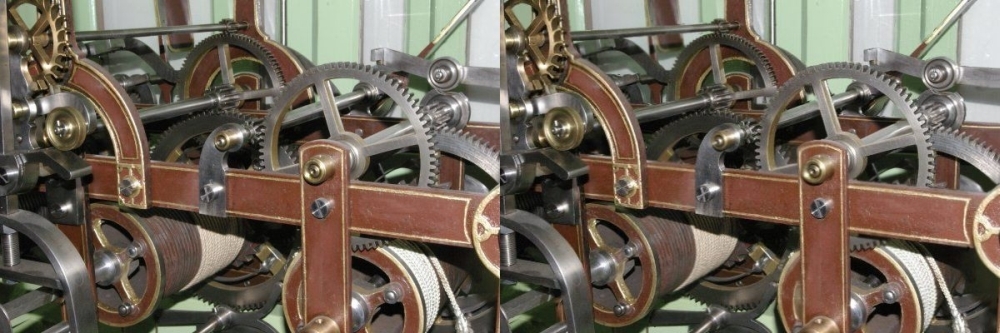

| Photo by Donald Simanek. |

Linderhof Palace (German: Schloss Linderhof) in southwest Bavaria. It is the smallest of the three palaces built by King Ludwig II of Bavaria and the only one which he lived to see completed. This was converted from a 2D picture taken with a Pentax SLR. This is the sort of scene that works well in 3d conversion.

| Photo by Donald Simanek. |

This is the mechanism of a large tower clock, taken at the Turmuhrenmuseum Mindelheim (Belfry clock museum of Mindelheim) in Bavaria. This would seem to be a severe challenge to conversion algorithms, but William3d handled the job splendidly. I haven't found any geometric errors in the complicated array of gears and shafts. Can you?

| Photo by Fred Bucheit. |

Here's another conversion sample by William3d. This 2D picture of me was taken by Fred Bucheit with a pocket digital camera, by available light at a public lecture. The picture included myself and another person, but I cropped this out and rotated it a bit, then sent it for 3d conversion. That's another advantage of post-production conversion. You can rotate the 2D picture by any amount before 3D conversion. You can't rotate a genuine stereo picture by more than a couple of degrees.

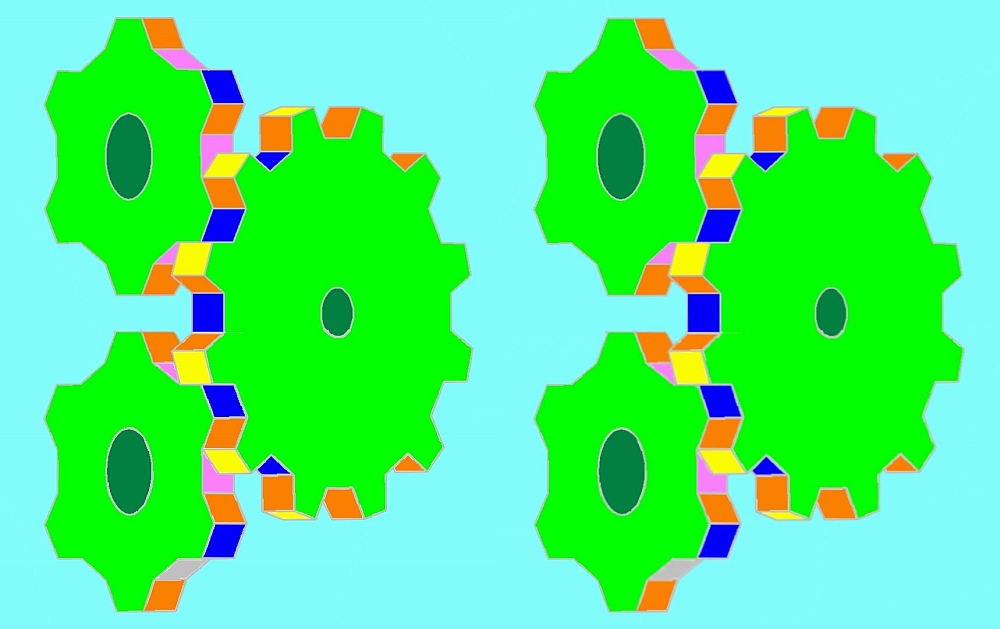

William and his staff at William3d.com clearly take customer satisfaction seriously. One of the pictures I sent for conversion was a severe test, one of my visual illusion drawings of impossibly intermeshed gears. The conversion failed to achieve my desired result, but William could not have known that. Even though I didn't ask, he went to the trouble of a doing a second conversion, which came out almost as I intended. You can see my own earlier 3D version, done the hard way by hand with a CAD program, on my 3D Illusions page.

| Illusion by Donald Simanek. |

Finally, a photo of historical interest. This is the reconstruction of the laboratory of Galileo Galilei, as imagined by the Deutsches Museum in Munich. His famous experiment, rolling a ball down an inclined plane, is in the foreground. The portraiat on the back wall is of Francesco I. de' Medici, from the original by Agnolo Bronzino. Galileo was tutor to the Medici children. The apparatus at the rear center is an armillary sphere, a device for calculating celestial coordinates.

| Photo by Donald Simanek. |

The photo above was taken with a Pentax SLR camera. The conversion was by William3d.com. The original was a bit dark, and had some convergence of verticals due to the camera angle. I corrected these myself before submitting the photo to William 3d for conversion. If an original has a bit of rotation problem, or is in need of cropping, I advise correcting that before conversion. I could find only one very minor glitch in the conversion, but it is only noticeable in the full size picture (I have reduced the size for this web page).

| Photo by Donald Simanek. |

This is another historic recreation at the Deutsches Museum, of the laboratory of the French Chemist Antoine Lavoisier. The large mirror is one he used to settle a bet whether sunlight could shatter a diamond. It did.

When you might need conversions.

In view of the high price of 2d to 3d conversion, who needs it? It is not likely to find a market for family snapshots. If you pay that much money the picture has to be worth it. There are some good reasons:

- Important pictures you took before you owned a 3d camera.

- Pictures that you took when you didn't have your 3d camera with you.

- Pictures you photographed in 2d, but have no opportunity to retake in 3d.

- Pictures that would have been near-impossible to make with a 3d camera.

- Action pictures in sporting events, not easily captured in 3d.

- Pictures involving complicated montages, double-exposures, and other "artsy" effects. Be aware these may be also near-impossible to convert to 3d. Some visual illusions that work in 2d simply can't be done in 3d. The conversion, if possible, might incur additional cost.

Does a photographer design the cameras used, and build them from scratch? Photographers used to do their own darkroom work, but most used commercial photofinishers. Few ever made their own film and sensitized paper (though a few did).

Did the artist or photographer create the beautiful nature scene he reproduces? Did the photographer grow and nurture that beautiful flower? Did the photographer arrange those clouds artistically? Did the photographer design and build that great piece of architecture in the photograph? Did Andy Warhol design that soup can he painted? Should Andy get credit for the painting? Did the can label designer get any credit or monetary reward when Andy sold the painting?

I've always been contemptuous of the "art" community's standards and values, which strike me as arbitrary and artificial. Some artists are able to make forgeries that even experts can't tell from the original. I can understand that this is a theft of intellectual property, not to be condoned. But what does it say about the self-proclaimed "experts" who sometimes can't tell the difference? The forger is borrowing an idea and a conception from the original artist, but also bringing a high level of skill and ingenuity to creating a result that successfully duplicates the paint, canvas, age and style of the original. That requires a skill level even the original artist may have been incapable of, and it ought to be worth some respect.

This "philosophical" issue really becomes tricky when you consider that the 2d to 3d process can, in principle, be used to convert an actual 3d stereo original to a "better" stereo result. Perhaps you wanted a greater interlens separation for enhanced depth, but your camera couldn't do it. If it were an action picture, the option of a cha-cha picture isn't available. A conversion could fix that and create a picture worthy of a prize! I don't know whether the conversion services have caught on to those possibilities yet, but I suspect one day they will.

Stereo pictures for cross-eyed viewing 3d Gallery One.

More cross-eyed stereos in 3d Gallery Two.

Stereo view cards in 3d Gallery Three.

Building a digital stereo close-up photography system in 3d Gallery Four.

Review of the Loreo stereo attachment 3d Gallery Five.

Review of the Loreo macro adapter, 3d Gallery Five B

The Loreo macro stereo attachment—improved 3d Gallery Five C.

The Loreo LIAC attachment as a 3d macro device, 3d Gallery Five D.

Wildlife photography in your backyard, 3d Gallery Six.

A home-built digital stereo camera using mirrors 3d Gallery Seven.

Stereo close-up photography in your garden 3d Gallery Eight.

Stereo photography in your aquarium 3d Gallery Nine.

Stereo digital infrared photography 3d Gallery Ten.

Wider angle stereo with the Loreo LIAC 3d Gallery ll. A failed experiment.

Review of the Fuji FinePix Real 3D W1 camera. 3d Gallery 12.

Macro attachment for the Fuji FinePix REAL 3D W1 camera. 3d gallery 13.

Panoramic stereo photography. 3d Gallery 14.

Tips for stereo photography with the Fuji 3d camera. 3d Gallery 15.

Mirror methods for stereo photography. 3d gallery 16.

The Fuji 3d macro adapter using mirrors, by Paul Turvill.

The Fuji 3d macro adapter with flash! 3d gallery 17.

Critters in stereo. 3d gallery 18

Wide angle stereo. 3d gallery 19.

Telephoto Stereo. 3d gallery 20.

Stereos from outer space. 3d gallery 22.

Review of the Panasonic Lumix 3d digital camera. 3d gallery 23.

Reverberant flash for shadowless lighting.

Digital stereo photography tricks and effects.

Shifty methods for taking stereo pictures.

Stereoscopy with two synchronized cameras by Mike Andrus.

Guidelines for Stereo Composition.

Return to the the 3d and illusions page.

Return to Donald Simanek's front page.